Friday, 22 May 1987: My Final Thoughts on South Africans and Their System

10:45 PM, UB Environmental Science Computer Room

This afternoon I finished writing up the stories of my South African travels from my notes. Most assuredly a cause for celebration. Obviously, there is much more I could have seen and done in South Africa. But after more than a year, my curiosity about the people and their messed-up system has worn thin. Not that there isn’t more to learn. Far from it. One problem was that much of it has become too predictable. How many tales of black indolence can I listen to? How many angry anti-government cynics can one endure? Of course, many South Africans of all races and political persuasions have messages worth hearing but in due time you hear many different messages which break down into a few general themes.

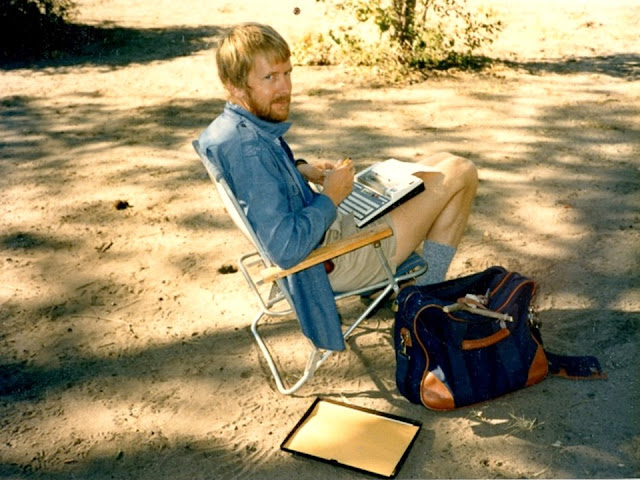

Writing in Chobe National Park, May 1987. My Botswana comrade, Hugh, once accused me of

being glued to my typewriter. I can’t

argue with his assessment! Photo by Hugh Gordon.

The situation in South Africa today is far from simple. It never has been ever since van Riebeeck put ashore from Table Bay in 1652. There are many angles from which to view it. I’ll put forth a few of them tonight.

Which is more important? The happiness and prosperity of less than 5 million whites or the same for nearly 30 million non-whites? The mathematics provide an obvious answer if one views it as an either-or question. Does it have to be an either-or question? Unfortunately, a majority of white voters look at it as an either-or situation as the recent white election results illustrate. But is this too simplistic? It’s probably more accurate to say that a majority of white people who vote for the ruling National Party candidates think that happiness and prosperity can be shared, but only on their terms. They feel that black folks are too simple and too gullible to know what is best for themselves and for the country.

The average “Nat”-supporter probably no longer considers the black African a child. Instead, he or she views him or her as a rebellious teenager who is perhaps ready to go out on a date but not reliable enough to be trusted with the family car (“the car” being the right to vote in national elections). One could perceive that white South Africans may come to see their black countrymen as “young adults” in another generation and even as equals in two. “It takes time to raise up the African,” they will tell you. “The world needs to be more patient.” An the more conservative whites will add that “the Africans were still in the trees less than a hundred years ago. [See, for example, the white inn-keeper’s rant in my story from 3-4 May 1986, “Other Countries Should Fix ‘Their Own Bloody Problems’.”]

However, with each year, the “world” is losing more and more its patience with South African stall tactics. Just how far “they” are willing to go to bring South Africa to heel is problematical. It must be noted that there is no united “they” against South African white supremacy either within or without.

Since I’m primarily writing for an American audience, perhaps I should focus on the United States official and unofficial policy toward South Africa. Too many Americans naively believe that sanctions and disinvestment will bring the white South African house of cards tumbling down. But there is a problem with this thinking: South Africa is not a house of cards; it’s an iron fortress defended by a determined people, many of whom sincerely believe they are in the right.

Like any iron fortress, there are weaknesses which can be exploited, but the price may be too high for the U.S. government and citizens to stomach. One weakness is South Africa’s mineral wealth – especially gold, diamonds, platinum, and cobalt. Stop buying it and you send shock waves through the South African economy. But that only works if EVERYONE stops buying it and that may be nigh on to impossible to achieve.

Even if sanctions did cause a major disruption in South Africa, the outcome might not be what we would expect with our naïve optimism that we can still change the world. A majority of white South Africans aren’t going to suddenly declare, “Okay, World, you’ve won. We give up,” just because the going gets tough. Instead, they’ll lay off (retrench, as they call it) thousands of black workers to cut costs and hire economically displaced whites, if it has to come to that. Under that scenario, once a significant number of blacks have no investment in the economic system, they may rebel in masse. That’s when the blood bath will start. Will significant numbers of white South African soldiers fire on their black brothers as the white police in Sharpeville did in 1960? I am skeptical that a mutiny within the army would happen even among the black troops. But if the situation gets bad enough, who knows? It doesn’t seem to me that white notions of racial superiority and the sanctity of Apartheid are the same as they were a generation ago. And I base that on the hundreds of whites I’ve spoken with over the past year.

If revolution does come, what about the black homeland armies and police? What about the Front Line States such as Botswana and Zimbabwe? Inevitably, they would be drawn into a major conflict. The result would be a regional war in southern Africa reaching north to the borers of Zaire and Tanzania. Thousands would be killed. The Western Allies and the Warsaw Pact would become involved, at least as suppliers of arms. It might be the first time since World War II that they agree on a common enemy. Eventually the white South African government would be brought to its knees but at a tremendous cost.

What if South Africa really does have “The Bomb”? Rest assured they will use it if they are losing badly. President Piet Botha and Foreign Minister Pik Botha might be shot and hung by their heels from a Soweto lamp post ala Mussolini, but the Front Line capitals would lie in ruins.

I think it doubtful such a scenario will develop because the U.S. and the Europeans will not push South Africa that far with limited economic sanctions. This is a half-hearted program which will make an important moral statement, but it probably won’t bring about the desired effect any more than our limited military adventure in Viet Nam did.

Perhaps there is little we Americans can do other than make moral statements. We can’t actively support black-nationalist terrorism against South Africa without looking like hypocrites. Nevertheless, a fine-tuned program of sophisticated terrorism directed against the South African Army and police would go a long way toward dampening the enthusiasm of young white South Africans to participate in a war against an unseen enemy. Against an inflexible laager, terrorism might prove to be the only weapon against the white man’s military machine short of full-scale warfare in southern Africa.

Baring a massive campaign of terrorism by black nationalists, what seems more likely is that so-called reforms will proceed slowly. More blacks will be given a piece of the action, but on the white man’s terms. For economic reasons, more blacks will join the ranks of collaborators as the National Party government holds out larger and larger carrots. The one carrot that they cannot hold out, of course, is one-man, one-vote, democratic majority rule. The whites in control seem to be convinced that such a move would mean the end of their culture. Better they should be damned by the world and struggle as poor farmers than live under a black-majority government.

Sanctions and disinvestment may be fine as moral statements. They may win us some friends in black Africa, but we should have no illusions that they will bring down the apartheid regime. If we expect too many tangible results from our expressions of moral outrage, we will set ourselves up for yet another disappointment in the arena of international politics.

And, when we are

expressing this outrage, we should take care not to get too self-righteous

about it. South African whites are quick

to point out that we’ve much to do to put our own racial house in order. While it is a clever ploy to get the monkey

on to other people’s backs, we still can’t seem to shake our own monkey of

racism and inequality. Few white South

Africans are the racist monsters some of us would like to believe they

are. They simply look after their own

interests first. Are most of us any

different? Would we do any better were

we in the same situation? Our shameful

history suggests that we would not. We

best not act overly smug toward South Africa lest someone point out that the flatulence

of our society has its own distinctly malodorous attributes!

Comments

Post a Comment